Curing Homesickness with Tok Daal

Content Warning: Pandemic

The recipe for Tok Daal is quite simple. My mother explained it to me in five short lines over WhatsApp, and it took me one quick trip to the nearest Indian store to get the ingredients –

· Unripe Mangoes

· Mustard Seeds

· Arhar Daal (Red Gram)

· Dried Red Chili

In India, I had never been to air-conditioned stores to buy such commonplace ingredients. Instead, we had open bazaars with divided sections. My favorite part of the market was always the fish aisle, especially in Kolkata Lansdowne Market. The fish aisle openly displayed a large variety of fishes: rohu, bhetki, boal, hilsa, tilapia, sol, tangra, gurjali, magur, mourala, and so many more. Now in the US, I still inadvertently end up lurking at the fish aisle in GrandMart or Walmart, even if I don’t mean to buy any.

Boil the lentils, preferably Arhar or red gram, and put them aside. Peel the mango and slice it into thin pieces. In a wok, add oil and heat it. Once it heats up, add a spoonful of mustard seeds and wait for them to splutter. Spluttering mustard or cumin seeds in hot oil lets out an aroma that hits home. Tossing dried red chilies directly into the hot oil makes the entire vicinity near the kitchen fill with smoke. But during lunchtime, when the dining table wears the delicious display of a 7-course meal, all that smoke seems worth it. My mother keeps up my grandmother’s tradition of feeding people. “Food is a clear display of affection,” she says. I believe her.

I used food to create a community for myself after I moved to the US when I was 24. In Norfolk, Virginia, the South Asian diaspora was relatively small, especially around the university where I lived. I used food to expose different people to my culture. Like my mother, I invited them over for food and chai. I introduced them to the glamor and extravaganza of Bollywood, as we indulged in conversations about religion, festivals, tradition, colonialism, and more. Before they knew it, they became a part of my culture and my family outside my family.

Once the mustard seeds splutter, add a couple of dried red chilies and fry them briefly in the oil. The chilies should not be left in the oil for too long or they will burn and set off the fire alarm. It’s quite common for the fire alarms to blast through the apartment when cooking Indian food.

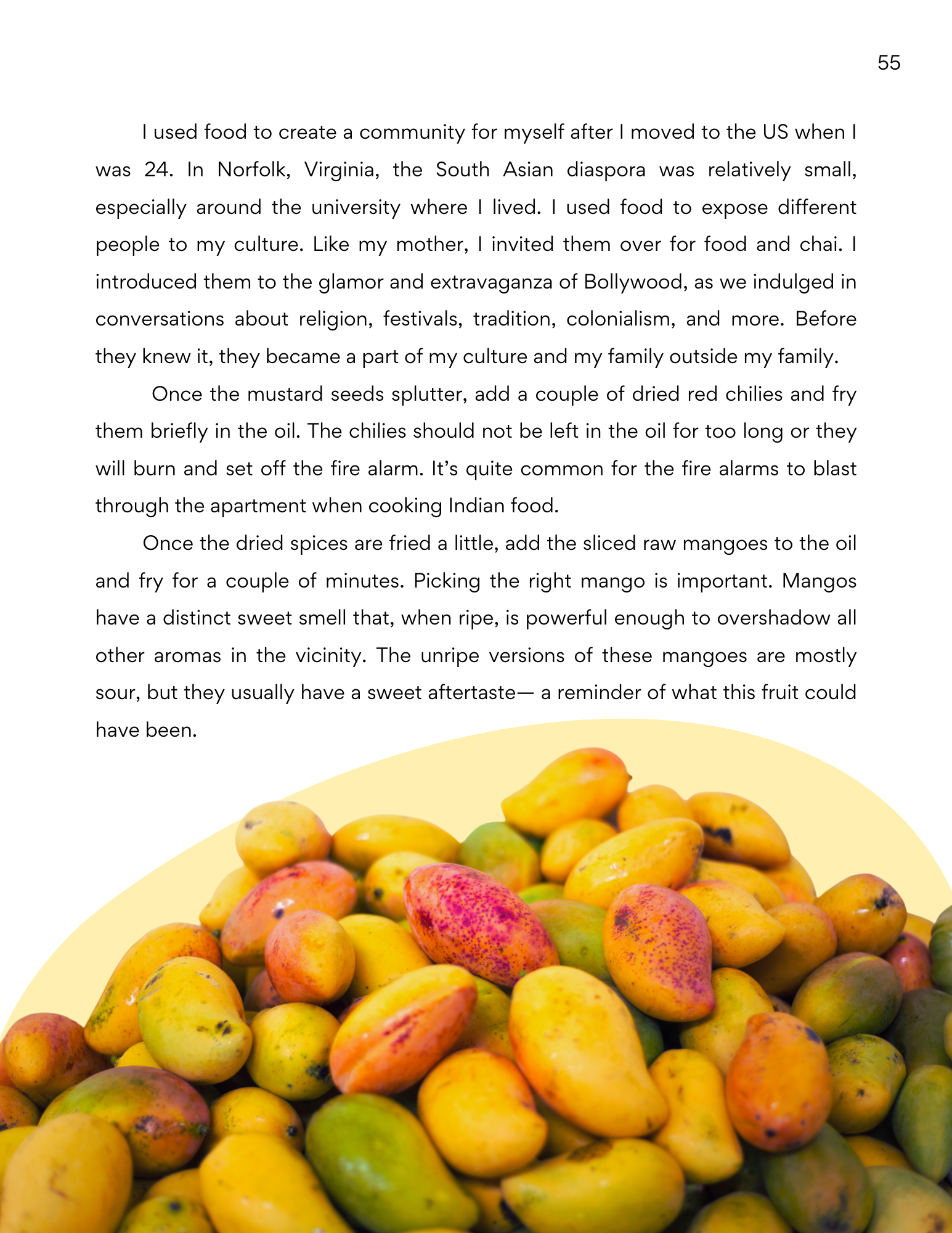

Once the dried spices are fried a little, add the sliced raw mangoes to the oil and fry for a couple of minutes. Picking the right mango is important. Mangos have a distinct sweet smell that, when ripe, is powerful enough to overshadow all other aromas in the vicinity. The unripe versions of these mangoes are mostly sour, but they usually have a sweet aftertaste— a reminder of what this fruit could have been.

Every year, during the summer holidays in Kolkata, my grandfather ensured a consistent supply of juicy summer fruits. The room adjacent to the kitchen, where raw vegetables and fruits were stored, overflowed in a perpetual bounty of mangoes, litchis, sugar palm fruits, and ripe jackfruits. My grandmother often refused to eat her share of these summer fruits. “Give it to the children,” she used to say.

Add the boiled lentils to the wok and give the entire thing a mix. The lentils need to blend with the fried whole spices and the raw mangoes. Now bring the mixture to a boil. Boiling will ensure that the taste of raw fried mangoes mingles evenly with every grain of lentils. Once the daal gains a thick texture, add sugar and salt for taste at the end. The sugar and salt have to be balanced; comfort food gives comfort when it equally satisfies all taste buds.

The first time I attempted to make tok daal was in the summer of 2020, amidst the ongoing pandemic. When homesickness began to dig its nails deep into my bones. I needed relief. After nearly 45 minutes, I had my tok daal prepared in front of me. At first, I was quite hesitant to taste my own food. Reluctantly, I took a bite. Not as good, but it had traces of my mother’s touch. The combination of all the flavors enhanced by the presence of the daal and mangoes managed to temporarily loosen the grasp of homesickness. I was motivated to try that recipe a couple of more times in the hopes of acquiring my mother’s magic. The kitchen was my lab, and I was the mad scientist.

Each iteration of tok daal had something new to offer, but always lacked the touch of home, the touch of my mother’s care: the way she soothes me back to sleep when I wake up from a nightmare and runs out in the sun to get sugarcane juice for me when I get back home from college in the scorching summer heat of India and holds me tight in her warm embrace when my heart shatters into a million pieces.

In everyday life, I try to imitate my mother. The way I tie my sari, add a spoon of sugar to balance the taste of everything I cook, read Tagore at the end of an exhausting day, fix the sofa cover as I walk past, fix my best friend’s hair, and fixate on cleaning the house. Like my mother, I find great pleasure in cooking for my loved ones. Like her, I can happily give up the last piece of mango to someone I love.