Birthday Suits

My Akka receives a package on her doorstep the morning of last Wednesday, and it is to small joy, for when she shakes it, it crinkles.

‘It is so sad,’ she informs the courier fellow who waits, bored, for her to mark her initials upon the proffered document with a needless flourish, which she performs with a smile that stretches her skin a little more than it once did. ‘How expensive these couture pieces are getting! But what to do, all my friends have at least seven! One for every day of the week! Can you imagine!’ To his clear regret, he cannot.

The box is taken to with scissors and a heavy hand. Cardboard lays discarded in big and small bits across the floor, and a wad of cream is lifted out of the delicate brown tissue, a product sustainability tag threaded through the earlobe, company brand stitched with fine gold thread into the underside. The material is sheer—flimsy—and carried straight into a cupboard that is steadily amassing yet a few more, different-coloured wads: these are not as sheer, and not as gentle, but not as not-sheer or not-gentle for it to matter for the moment. The wears may be remedied swiftly with a small touch-up of tint, and the wrinkles, simply ironed away with a minute under a hot press set to a point between silk and nylon.

Akka is not as rich as her friends, who boast often of their seven skins; she plans to go hungry for a month to pay for this expense. It is a great opportunity, she tells me, to shed a few kilos, but not so many that there may be nothing to hold the new stitch upon her in the first place.

For my birthday—which is to arrive in a week—she wins me the lottery, the prize of which is a free consultation with Sui Mamiji, world-famous seamstress and part-time cosmetologist, and a twenty per cent discount coupon for first purchases. ‘Sui Mamiji will know exactly what to do with you,’ she tells me, sweet, jealous, smoothing back my hair with a hand that’s currently burnt caramel. Golden bangles jingle. Her palms make clammy, sticky sounds when they fold at the creases, and quickly, she shoves them into the pockets of her dress. ‘You know,’ she tells me, ‘she is famous for her impeccable cuts and exact measurements. Here, pull up your sleeve, look how slack it is getting on you! Do you not agree that it is time for a wardrobe change?’

I tug the sleeve of the birthday suit over my shoulder, and it tightens across my neck like a noose. I think, perhaps such a thought is ungrateful to think.

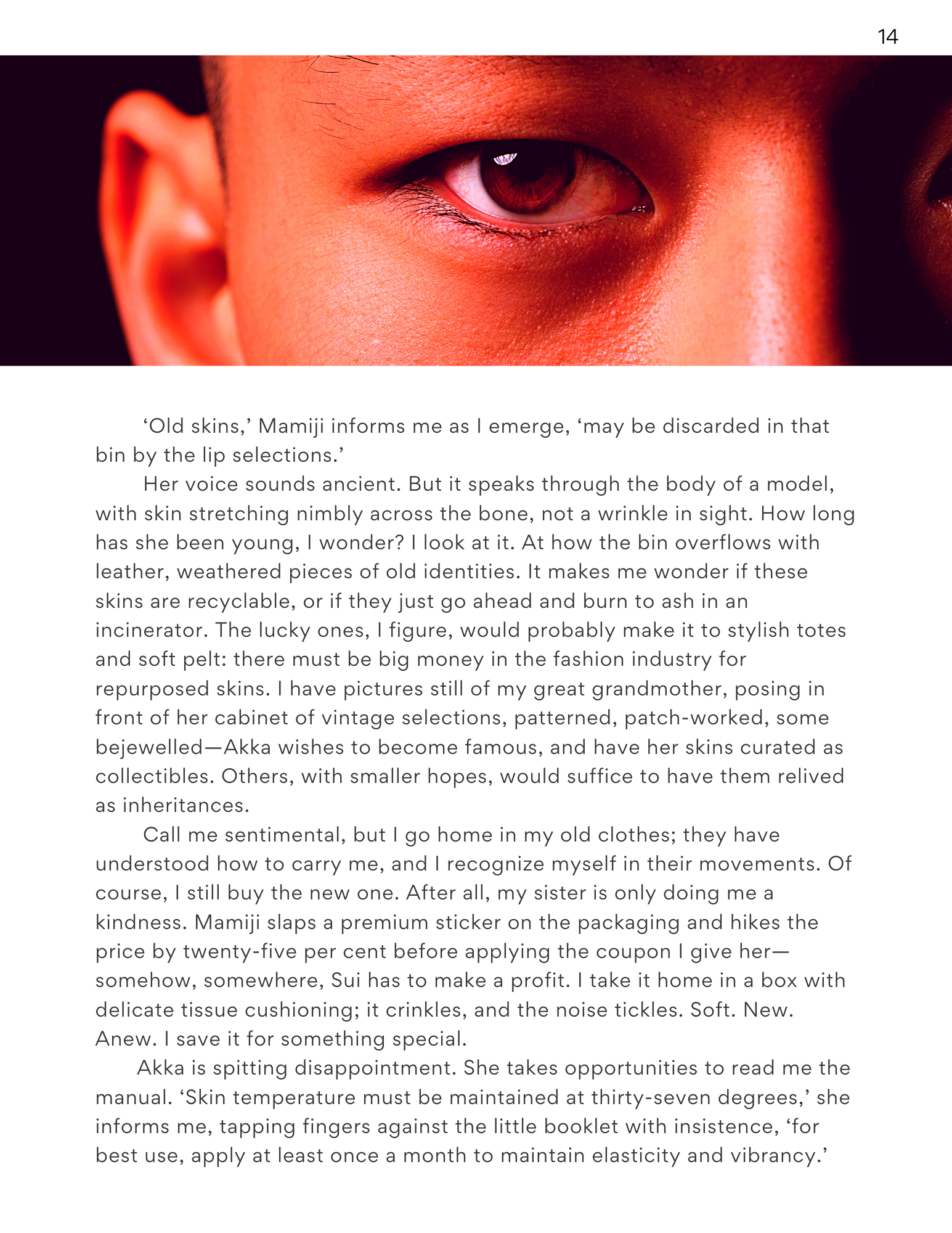

It is easier still, I suppose, to think about everything but the reflection I am pressing into the mirror. The walls of the fitting room, for example, are a putrid pink, with aging cracks tucked behind poorly-matched patches. Names are scratched across it, tiny we-were-here’s before they were no longer them, and fingerprint smudges, as if attempts to see what new shapes a new hand can make. Do they swirl in beautiful ways? Do they feel like they belong? There is more. There is dried drool from licks of a tongue, indents from nails, bile, and blood and lip stains—look at all these bodies kissing secondhand.

With a scrunching nose, I pay more attention to my reflection, the way it plays with my undertones. Like sediment, it feels heavy in the newness, but Akka, stuffing her eyes through the crack in the door jamb, assures me that it is ‘very becoming, the perfect size, now don’t go breaking your head about it.’

I turn and crane my neck as far as it can. Brush stubby fingers across the dimples on my back. The hinge of my knees. The rubbery pinch between my index and thumb. My elbows, artfully darkened patches, nudging against the curve of my waist—toes, crinkling, nerve endings squirming to familiarize themselves with the new envelope—my abdomen shifts ever so slightly and I press it with my fingers to keep it steady inside me.

Naked, I think, changes when skin is changeable. It feels strange. Like I’m being possessed. Like I’m possessing someone else. How does Akka do it?

My sister pish-poshes, she tells me that it’s normal for it to feel like this. The colour is quite lovely: an airbrushed honey, a few yellows from what I’m used to seeing upon me, but close enough that no one would put in the effort to notice the difference. Akka, I know, is wishing that I would go all out with something more exotic.

But I cannot help but cast my gaze at my old skin, which lays discarded upon the bench. It is a used, shrivelled sock with many faults and freckles—and I am well familiar with the details. With ever scar, peppering across the expanse from old falls and injuries, with every blemish, somehow harsher and redder as they crumple into themselves. The sleeves that once gloved my arms dangle, fingertips trailing the ground with a bizarre lifelessness.

‘Vehl?’ I hear Mamiji ask. ‘Does she like?’ More skins slap against glass surfaces as ladies look for perfect shades and stretches. More curtains rustle. In each fitting room, a woman struggling to contain herself.

The store, in the meantime, is full of shop talk. ‘But where is that lovely beige we saw just now—?’

‘—no, no, that will hardly suit your eyes, here, try this shade of deodar, it is a hot piece nowadays, selling fast—’

‘—I think that she likes it,’ Akka is saying, the familiarity of her voice cutting through the bustle, ‘but I am not 100% sure—’

‘—what bakwaas!’ a voice is shrill. ‘It’s so dark! Tell me, where are your pieces from the Fair & Lovely line? You had some nice white ones last time we saw!’

‘Sold out, madam, all the fair ones go first—’

‘—arey, but we are going for vacation to the foreign, you know, when will you have more—?’

‘—we restock every Monday—’

‘—but that is too late! What shame!’

My new skin, in sharp contrast, is clean. Faultless. There is a light dusting of fashionable body hair upon an ocean of evenly distributed melanin, and the palms of these hands are tender, liberated from callouses. I run my hand against my breast. Against the rounded brown nubs. Perfectly positioned. The dip in my bellybutton, perfectly circular. I feel the tight skin of my stomach, and thin trail of hair that travels downward—and below it, the faint serrations of teeth on a zipper, tucked into the folds that follow; it fits me well enough. Or perhaps better put, I seem well to fit it—

‘—she’ll take it, I’m sure—’

—and the fingertips dangle still; I feel them with the ones I’m wearing at the moment. I compare the fingerprints; the way they sketch out different patterns. The moment hangs in the air. As if old and new versions of me are meeting as discrete individuals.

I hesitate.

‘Well?’ Akka sounds impatient.

‘It’s great,’ I say, barely audible over the young woman in the fitting room next to me who is complaining of her mulberry vagina, demanding her mother to pick up one of the premium options. ‘Thanks.’

‘Anything for the birthday girl,’ Akka says, thrilled to pieces.

‘Old skins,’ Mamiji informs me as I emerge, ‘may be discarded in that bin by the lip selections.’

Her voice sounds ancient. But it speaks through the body of a model, with skin stretching nimbly across the bone, not a wrinkle in sight. How long has she been young, I wonder? I look at it. At how the bin overflows with leather, weathered pieces of old identities. It makes me wonder if these skins are recyclable, or if they just go ahead and burn to ash in an incinerator. The lucky ones, I figure, would probably make it to stylish totes and soft pelt: there must be big money in the fashion industry for repurposed skins. I have pictures still of my great grandmother, posing in front of her cabinet of vintage selections, patterned, patch-worked, some bejewelled—Akka wishes to become famous, and have her skins curated as collectibles. Others, with smaller hopes, would suffice to have them relived as inheritances.

Call me sentimental, but I go home in my old clothes; they have understood how to carry me, and I recognize myself in their movements. Of course, I still buy the new one. After all, my sister is only doing me a kindness. Mamiji slaps a premium sticker on the packaging and hikes the price by twenty-five per cent before applying the coupon I give her—somehow, somewhere, Sui has to make a profit. I take it home in a box with delicate tissue cushioning; it crinkles, and the noise tickles. Soft. New. Anew. I save it for something special.

Akka is spitting disappointment. She takes opportunities to read me the manual. ‘Skin temperature must be maintained at thirty-seven degrees,’ she informs me, tapping fingers against the little booklet with insistence, ‘for best use, apply at least once a month to maintain elasticity and vibrancy.’ She feeds me statistics by the handsful. ‘Skins lose their adhesiveness at the rate of 0.05 per cent per day without regular application!’ ‘Since when did you stop wanting to look full beautiful?’

But it is not like I do not follow the instructions. I take it to the bath and wash it with coconut exfoliate. I rub jojoba oil into the creases, and watch sewing tutorials when it begins to wear at the shins. I put it on once a month and smile at every compliment.

It’s a pity that it isn’t enough for Akka, who works her way up to seven skins, and continues to express her disapproval through gaunt cheekbones and sunken lips.

One birthday later, I wake up to my nerves screaming, my skin burning; I am forced to make the change permanent. ‘It is for your own good,’ my sister tells me, righteous. ‘Look at you! It becomes you well.’

She is only doing me a kindness.